Kristina Guild Douglass (Anthropology) spent 10 years of her childhood in Madagascar, and now does her dissertation fieldwork there. Set in the Indian Ocean off the coast of Southeast Africa, Madagascar is the fourth-largest island in the world.

<p>

It split from India around 88 million years ago, following the prehistoric breakup of the supercontinent Gondwana. Native plants and animals evolved there in relative isolation, and over 90 percent of its wildlife is found nowhere else. Humans came to the island fairly recently, with multiple waves of migration over the last few thousand years from around the Indian Ocean and as far away as Indonesia. Since the arrival of man, several megafauna such as elephant birds, pigmy hippos, and man-sized lemurs have become extinct.

<p>

“As the world enters into a new wave a mass extinctions, which is starting to announce itself with the precarious status of species like the black rhino, it is very important to understand how human action is linked to ecology, evolution, and climate change,” says Kristina.

<p>

Through archaeological surveys and excavations along the coast, Kristina aims to establish the chronology of human settlement for the Bay of Antsaragnasoa. She hopes to clarify the patterns of trade and exchange between this region and the wider Western Indian Ocean and document the interactions among human communities as well as their impact on the environment. Her interest in how people and places interact goes back to her childhood. Kristina was born in Lomé, Togo, and has three siblings adopted from Ethiopia, Eritrea, and Madagascar.

<p>

“We were each born to different parents in different African countries and adopted under difficult circumstances: civil war in the case of my sister and youngest brother. Our adoptive parents began their international careers as Peace Corps volunteers and later worked in the public health and development sectors in Ukraine, Senegal, Kenya, Cameroon, Madagascar, and other countries, primarily in Sub-Saharan Africa. As a result of their many posts and assignments, my siblings and I studied in different school systems and learned new languages as we moved from country to country. Though our distinct backgrounds and histories pose challenges that many families do not face, our experiences together have forged my belief that the past is a universally meaningful construct and that peoples’ relationship with the past is as important to study as the past itself.

<p>

“Madagascar, where my family lived for 10 years, is where I first developed a conscious sense of how peoples’ relationship to the past can impact the present and future,” she says. Over the course of two years, she and fellow students learned about development issues, in class and on field trips. “We observed both success and failure as conservationists and development agencies tackled deforestation, poverty, and other difficult issues.” This experience “planted a seed in my mind that has led me to integrate my archaeological research with community-based efforts at marine conservation and sustainable development.”

<p>

Her current research, advised by Roderick McIntosh, takes her to a beautiful but remote dry spot in the Spiny Forest, “a 10-hours’ drive from the nearest big town on a good day.” Her base camp is in the tiny fishing village of Andavadoaka, walking distance to sites she studies. She and her team work on excavations or surveys from 7:30 a.m. until 5:30 p.m., then carry all of the equipment back to base and work in the lab for a few more hours. “As a field director my days are very long, as I also deal with all of the accounting, logistical and research planning, managing the team, and anything that comes up on a day-to-day basis,” she says.

<p>

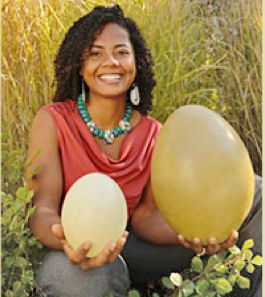

One focus of her dissertation project is the interaction between people and the now-extinct giant elephant bird, Aepyornis, the largest of which stood over 10 feet tall, weighed up to 800 pounds, and laid eggs 160 times the volume of a chicken egg. The National Geographic Society in Washington has an intact subfossilized egg that contains an embryonic skeleton of the unborn bird.

<p>

“When they died out is a central question of my research,” she says. “There may have been five or more species of these birds in Madagascar, and each species likely had a distinct extinction trajectory.” The last historical sighting of an Aepyornis was in the 17th century, and most of the radiocarbon-dated remains hover around the 12th century or earlier, but Kristina has found a specimen that may be much younger – in fact, if she can confirm the date, it would be the youngest elephant bird remains ever discovered.

<p>

“Why they died out is also a complex question, but the answer is somewhere in the combination of climate change, changes in vegetation patterns, and human predation,” she says. “From my excavations, however, human predation seems to be limited to egg-poaching. I have not found any evidence that people hunted adult birds, which was one of the major drivers of extinction for giant flightless birds elsewhere, like the moa in New Zealand.”

<p>

Over several seasons, she has recovered rare evidence of direct human interaction with these birds, including the first documented eggshell beads. Using a scanning electron microscope, she is able to distinguish between eggshells that hatched naturally and those broken open by people. “This should tell us more about whether and how people ate these large eggs. Other than food, there are ethnographic examples of people using the egg shells as drinking containers for water and for exporting rum to nearby islands like Mauritius.”

<p>

Kristina will be returning to Madagascar this spring to do additional fieldwork and begin to integrate her archaeological research into development and conservation initiatives in the region. She recently submitted a proposal in collaboration with Blue Ventures, a marine conservation organization working in Madagascar, that aims to help alleviate the poverty, increasing difficulty of making a living from fishing, and severe degradation of marine environments due to over-exploitation. Her project will develop a model for managing community-based archaeological resources that integrates archaeological sites into local eco-tourism offerings and provides local youth with hands-on scientific learning.

<p>

When home in New Haven, Kristina trains and performs capoeira – an Afro-Brazilian martial art – and samba. She also sings in a samba band with her husband Scott, who plays the acoustic bass. They have a one-year-old Rhodesian Ridgeback named Dart and two cats, Matiu and Samba.

<p>